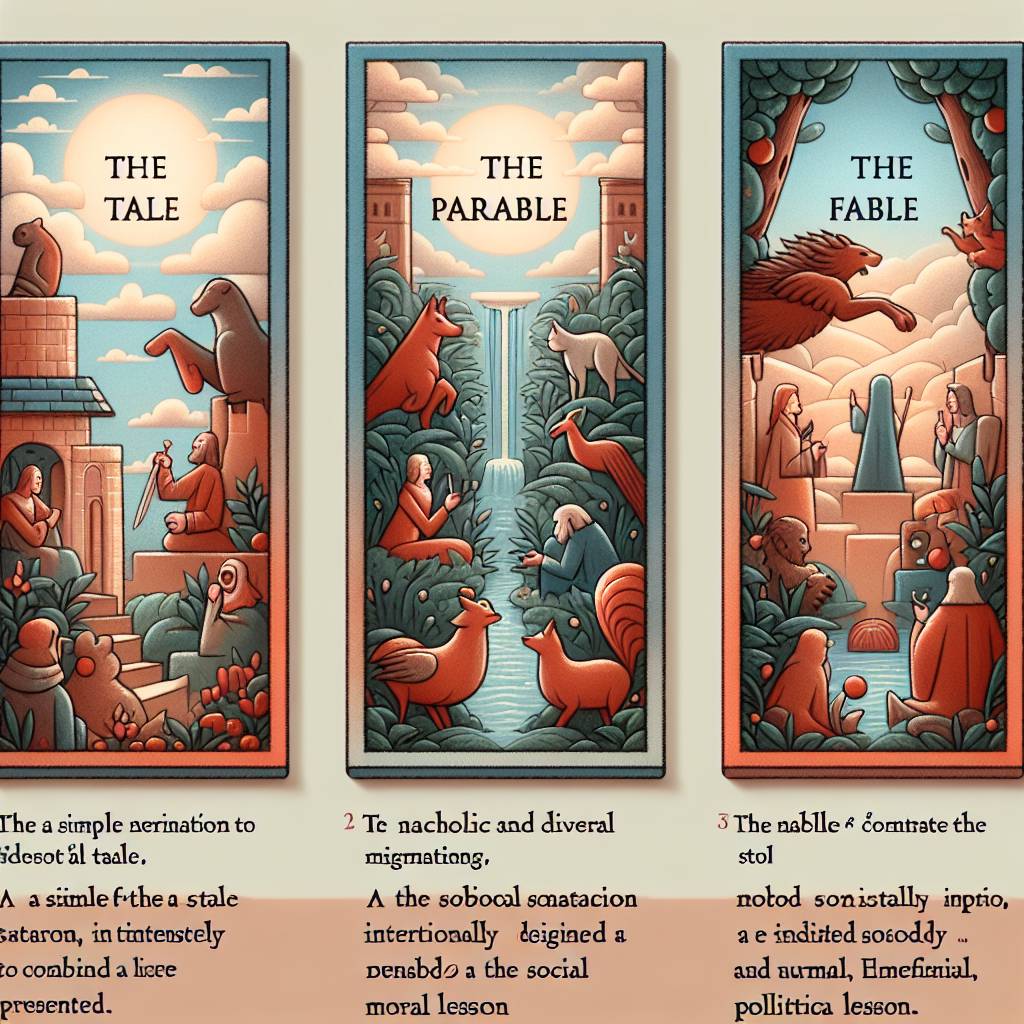

THE TALE, the Parable, and the Fable are all common and popular modes of conveying instruction. —

Each is distinguished by its own special characteristics. —

The Tale consists simply in the narration of a story either founded on facts, or created solely by the imagination, and not necessarily associated with the teaching of any moral lesson. —

The Parable is the designed use of language purposely intended to convey a hidden and secret meaning other than that contained in the words themselves; —

and which may or may not bear a special reference to the hearer, or reader. —

The Fable partly agrees with, and partly differs from both of these. —

It will contain, like the Tale, a short but real narrative; —

it will seek, like the Parable, to convey a hidden meaning, and that not so much by the use of language, as by the skilful introduction of fictitious characters; —

and yet unlike to either Tale or Parable, it will ever keep in view, as its high prerogative, and inseparable attribute, the great purpose of instruction, and will necessarily seek to inculcate some moral maxim, social duty, or political truth. —

The true Fable, if it rise to its high requirements, ever aims at one great end and purpose representation of human motive, and the improvement of human conduct, and yet it so conceals its design under the disguise of fictitious characters, by clothing with speech the animals of the field, the birds of the air, the trees of the wood, or the beasts of the forest, that the reader shall receive advice without perceiving the presence of the adviser. —

Thus the superiority of the counsellor, which often renders counsel unpalatable, is kept out of view, and the lesson comes with the greater acceptance when the reader is led, unconsciously to himself, to have his sympathies enlisted in behalf of what is pure, honorable, and praiseworthy, and to have his indignation excited against what is low, ignoble, and unworthy. —

The true fabulist, therefore, discharges a most important function. —

He is neither a narrator, nor an allegorist. —

He is a great teacher, a corrector of morals, a censor of vice, and a commender of virtue. —

In this consists the superiority of the Fable over the Tale or the Parable. —

The fabulist is to create a laugh, but yet, under a merry guise, to convey instruction. —

Phaedrus, the great imitator of Aesop, plainly indicates this double purpose to be the true office of the writer of fables.

Duplex libelli dos est: quod risum movet,

Et quod prudenti vitam consilio monet.

The continual observance of this twofold aim creates the charm, and accounts for the universal favor, of the fables of Aesop. “The fable,” says Professor K. O. Mueller, “originated in Greece in an intentional travestie of human affairs. —

The ‘ainos,’ as its name denotes, is an admonition, or rather a reproof veiled, either from fear of an excess of frankness, or from a love of fun and jest, beneath the fiction of an occurrence happening among beasts; —

and wherever we have any ancient and authentic account of the Aesopian fables, we find it to be the same.” 1

The construction of a fable involves a minute attention to (1) the narration itself; —

(2) the deduction of the moral; —

and (3) a careful maintenance of the individual characteristics of the fictitious personages introduced into it. —

The narration should relate to one simple action, consistent with itself, and neither be overladen with a multiplicity of details, nor distracted by a variety of circumstances. —

The moral or lesson should be so plain, and so intimately interwoven with, and so necessarily dependent on, the narration, that every reader should be compelled to give to it the same undeniable interpretation. —

The introduction of the animals or fictitious characters should be marked with an unexceptionable care and attention to their natural attributes, and to the qualities attributed to them by universal popular consent. —

The Fox should be always cunning, the Hare timid, the Lion bold, the Wolf cruel, the Bull strong, the Horse proud, and the Ass patient. —

Many of these fables are characterized by the strictest observance of these rules. —

They are occupied with one short narrative, from which the moral naturally flows, and with which it is intimately associated. —

“’Tis the simple manner,” says Dodsley, 2 “in which the morals of Aesop are interwoven with his fables that distinguishes him, and gives him the preference over all other mythologists. —

His ‘Mountain delivered of a Mouse,’ produces the moral of his fable in ridicule of pompous pretenders; —

and his Crow, when she drops her cheese, lets fall, as it were by accident, the strongest admonition against the power of flattery. —

There is no need of a separate sentence to explain it; —

no possibility of impressing it deeper, by that load we too often see of accumulated reflections. —

” 3 An equal amount of praise is due for the consistency with which the characters of the animals, fictitiously introduced, are marked. —

While they are made to depict the motives and passions of men, they retain, in an eminent degree, their own special features of craft or counsel, of cowardice or courage, of generosity or rapacity.

These terms of praise, it must be confessed, cannot be bestowed on all the fables in this collection. —

Many of them lack that unity of design, that close connection of the moral with the narrative, that wise choice in the introduction of the animals, which constitute the charm and excellency of true Aesopian fable. —

This inferiority of some to others is sufficiently accounted for in the history of the origin and descent of these fables. —

The great bulk of them are not the immediate work of Aesop. Many are obtained from ancient authors prior to the time in which he lived. —

Thus, the fable of the “Hawk and the Nightingale” is related by Hesiod; —

4 the “Eagle wounded by an Arrow, winged with its own Feathers,” by Aeschylus; —

5 the “Fox avenging his wrongs on the Eagle,” by Archilochus. —

6 Many of them again are of later origin, and are to be traced to the monks of the middle ages: —

and yet this collection, though thus made up of fables both earlier and later than the era of Aesop, rightfully bears his name, because he composed so large a number (all framed in the same mould, and conformed to the same fashion, and stamped with the same lineaments, image, and superscription) as to secure to himself the right to be considered the father of Greek fables, and the founder of this class of writing, which has ever since borne his name, and has secured for him, through all succeeding ages, the position of the first of moralists.7

The fables were in the first instance only narrated by Aesop, and for a long time were handed down by the uncertain channel of oral tradition. —

Socrates is mentioned by Plato 8 as having employed his time while in prison, awaiting the return of the sacred ship from Delphos which was to be the signal of his death, in turning some of these fables into verse, but he thus versified only such as he remembered. —

Demetrius Phalereus, a philosopher at Athens about 300 B.C., is said to have made the first collection of these fables. —

Phaedrus, a slave by birth or by subsequent misfortunes, and admitted by Augustus to the honors of a freedman, imitated many of these fables in Latin iambics about the commencement of the Christian era. —

Aphthonius, a rhetorician of Antioch, A.D. 315, wrote a treatise on, and converted into Latin prose, some of these fables. —

This translation is the more worthy of notice, as it illustrates a custom of common use, both in these and in later times. —

The rhetoricians and philosophers were accustomed to give the Fables of Aesop as an exercise to their scholars, not only inviting them to discuss the moral of the tale, but also to practice and to perfect themselves thereby in style and rules of grammar, by making for themselves new and various versions of the fables. —

Ausonius, 9 the friend of the Emperor Valentinian, and the latest poet of eminence in the Western Empire, has handed down some of these fables in verse, which Julianus Titianus, a contemporary writer of no great name, translated into prose. —

Avienus, also a contemporary of Ausonius, put some of these fables into Latin elegiacs, which are given by Nevelet (in a book we shall refer to hereafter), and are occasionally incorporated with the editions of Phaedrus.

Seven centuries elapsed before the next notice is found of the Fables of Aesop. During this long period these fables seem to have suffered an eclipse, to have disappeared and to have been forgotten; —

and it is at the commencement of the fourteenth century, when the Byzantine emperors were the great patrons of learning, and amidst the splendors of an Asiatic court, that we next find honors paid to the name and memory of Aesop. Maximus Planudes, a learned monk of Constantinople, made a collection of about a hundred and fifty of these fables. —

Little is known of his history. —

Planudes, however, was no mere recluse, shut up in his monastery. —

He took an active part in public affairs. —

In 1327 A.D. he was sent on a diplomatic mission to Venice by the Emperor Andronicus the Elder. This brought him into immediate contact with the Western Patriarch, whose interests he henceforth advocated with so much zeal as to bring on him suspicion and persecution from the rulers of the Eastern Church. —

Planudes has been exposed to a two-fold accusation. —

He is charged on the one hand with having had before him a copy of Babrias (to whom we shall have occasion to refer at greater length in the end of this Preface), and to have had the bad taste “to transpose,” or to turn his poetical version into prose: —

and he is asserted, on the other hand, never to have seen the Fables of Aesop at all, but to have himself invented and made the fables which he palmed off under the name of the famous Greek fabulist. —

The truth lies between these two extremes. —

Planudes may have invented some few fables, or have inserted some that were current in his day; —

but there is an abundance of unanswerable internal evidence to prove that he had an acquaintance with the veritable fables of Aesop, although the versions he had access to were probably corrupt, as contained in the various translations and disquisitional exercises of the rhetoricians and philosophers. —

His collection is interesting and important, not only as the parent source or foundation of the earlier printed versions of Aesop, but as the direct channel of attracting to these fables the attention of the learned.

The eventual re-introduction, however, of these Fables of Aesop to their high place in the general literature of Christendom, is to be looked for in the West rather than in the East. The calamities gradually thickening round the Eastern Empire, and the fall of Constantinople, 1453 A.D. combined with other events to promote the rapid restoration of learning in Italy; —

and with that recovery of learning the revival of an interest in the Fables of Aesop is closely identified. —

These fables, indeed, were among the first writings of an earlier antiquity that attracted attention. —

They took their place beside the Holy Scriptures and the ancient classic authors, in the minds of the great students of that day. —

Lorenzo Valla, one of the most famous promoters of Italian learning, not only translated into Latin the Iliad of Homer and the Histories of Herodotus and Thucydides, but also the Fables of Aesop.

These fables, again, were among the books brought into an extended circulation by the agency of the printing press. —

Bonus Accursius, as early as 1475-1480, printed the collection of these fables, made by Planudes, which, within five years afterwards, Caxton translated into English, and printed at his press in West — minster Abbey, 1485. —

10 It must be mentioned also that the learning of this age has left permanent traces of its influence on these fables, 11 by causing the interpolation with them of some of those amusing stories which were so frequently introduced into the public discourses of the great preachers of those days, and of which specimens are yet to be found in the extant sermons of Jean Raulin, Meffreth, and Gabriel Barlette. —

12 The publication of this era which most probably has influenced these fables, is the “Liber Facetiarum,” 13 a book consisting of a hundred jests and stories, by the celebrated Poggio Bracciolini, published A.D. 1471, from which the two fables of the “Miller, his Son, and the Ass,” and the “Fox and the Woodcutter,” are undoubtedly selected.

The knowledge of these fables rapidly spread from Italy into Germany, and their popularity was increased by the favor and sanction given to them by the great fathers of the Reformation, who frequently used them as vehicles for satire and protest against the tricks and abuses of the Romish ecclesiastics. —

The zealous and renowned Camerarius, who took an active part in the preparation of the Confession of Augsburgh, found time, amidst his numerous avocations, to prepare a version for the students in the university of Tubingen, in which he was a professor. —

Martin Luther translated twenty of these fables, and was urged by Melancthon to complete the whole; —

while Gottfried Arnold, the celebrated Lutheran theologian, and librarian to Frederick I, king of Prussia, mentions that the great Reformer valued the Fables of Aesop next after the Holy Scriptures. —

In 1546 A.D. the second printed edition of the collection of the Fables made by Planudes, was issued from the printing-press of Robert Stephens, in which were inserted some additional fables from a MS. in the Bibliotheque du Roy at Paris.

The greatest advance, however, towards a re-introduction of the Fables of Aesop to a place in the literature of the world, was made in the early part of the seventeenth century. —

In the year 1610, a learned Swiss, Isaac Nicholas Nevelet, sent forth the third printed edition of these fables, in a work entitled “Mythologia Aesopica. —

” This was a noble effort to do honor to the great fabulist, and was the most perfect collection of Aesopian fables ever yet published. —

It consisted, in addition to the collection of fables given by Planudes and reprinted in the various earlier editions, of one hundred and thirty-six new fables (never before published) from MSS. in the Library of the Vatican, of forty fables attributed to Aphthonius, and of forty-three from Babrias. —

It also contained the Latin versions of the same fables by Phaedrus, Avienus, and other authors. —

This volume of Nevelet forms a complete “Corpus Fabularum Aesopicarum; —

” and to his labors Aesop owes his restoration to universal favor as one of the wise moralists and great teachers of mankind. —

During the interval of three centuries which has elapsed since the publication of this volume of Nevelet’s, no book, with the exception of the Holy Scriptures, has had a wider circulation than Aesop’s Fables. —

They have been translated into the greater number of the languages both of Europe and of the East, and have been read, and will be read, for generations, alike by Jew, Heathen, Mohammedan, and Christian. —

They are, at the present time, not only engrafted into the literature of the civilized world, but are familiar as household words in the common intercourse and daily conversation of the inhabitants of all countries.

This collection of Nevelet’s is the great culminating point in the history of the revival of the fame and reputation of Aesopian Fables. —

It is remarkable, also, as containing in its preface the germ of an idea, which has been since proved to have been correct by a strange chain of circumstances. —

Nevelet intimates an opinion, that a writer named Babrias would be found to be the veritable author of the existing form of Aesopian Fables. —

This intimation has since given rise to a series of inquiries, the knowledge of which is necessary, in the present day, to a full understanding of the true position of Aesop in connection with the writings that bear his name.

The history of Babrias is so strange and interesting, that it might not unfitly be enumerated among the curiosities of literature. —

He is generally supposed to have been a Greek of Asia Minor, of one of the Ionic Colonies, but the exact period in which he lived and wrote is yet unsettled. —

He is placed, by one critic, 14 as far back as the institution of the Achaian League, B.C. 250; —

by another as late as the Emperor Severus, who died A.D. 235; —

while others make him a contemporary with Phaedrus in the time of Augustus. —

At whatever time he wrote his version of Aesop, by some strange accident it seems to have entirely disappeared, and to have been lost sight of. —

His name is mentioned by Avienus; —

by Suidas, a celebrated critic, at the close of the eleventh century, who gives in his lexicon several isolated verses of his version of the fables; —

and by John Tzetzes, a grammarian and poet of Constantinople, who lived during the latter half of the twelfth century. —

Nevelet, in the preface to the volume which we have described, points out that the Fables of Planudes could not be the work of Aesop, as they contain a reference in two places to “Holy monks,” and give a verse from the Epistle of St. James as an “Epimith” to one of the fables, and suggests Babrias as their author. —

Francis Vavassor, 15 a learned French jesuit, entered at greater length on this subject, and produced further proofs from internal evidence, from the use of the word Piraeus in describing the harbour of Athens, a name which was not given till two hundred years after Aesop, and from the introduction of other modern words, that many of these fables must have been at least committed to writing posterior to the time of Aesop, and more boldly suggests Babrias as their author or collector. —

16 These various references to Babrias induced Dr. Plichard Bentley, at the close of the seventeenth century, to examine more minutely the existing versions of Aesop’s Fables, and he maintained that many of them could, with a slight change of words, be resolved into the Scazonic 17 iambics, in which Babrias is known to have written: —

and, with a greater freedom than the evidence then justified, he put forth, in behalf of Babrias, a claim to the exclusive authorship of these fables. —

Such a seemingly extravagant theory, thus roundly asserted, excited much opposition. —

Dr. Bentley 18 met with an able antagonist in a member of the University of Oxford, the Hon. Mr. Charles Boyle, 19 afterwards Earl of Orrery. —

Their letters and disputations on this subject, enlivened on both sides with much wit and learning, will ever bear a conspicuous place in the literary history of the seventeenth century. —

The arguments of Dr. Bentley were yet further defended a few years later by Mr. Thomas Tyrwhitt, a well-read scholar, who gave up high civil distinctions that he might devote himself the more unreservedly to literary pursuits. —

Mr. Tyrwhitt published, A.D. 1776, a Dissertation on Babrias, and a collection of his fables in choliambic meter found in a MS. in the Bodleian Library at Oxford. —

Francesco de Furia, a learned Italian, contributed further testimony to the correctness of the supposition that Babrias had made a veritable collection of fables by printing from a MS. contained in the Vatican library several fables never before published. —

In the year 1844, however, new and unexpected light was thrown upon this subject. —

A veritable copy of Babrias was found in a manner as singular as were the MSS. of Quinctilian’s Institutes, and of Cicero’s Orations by Poggio in the monastery of St. Gall A.D. 1416. —

M. Menoides, at the suggestion of M. Villemain, Minister of Public Instruction to King Louis Philippe, had been entrusted with a commission to search for ancient MSS., and in carrying out his instructions he found a MS. at the convent of St. Laura, on Mount Athos, which proved to be a copy of the long suspected and wished-for choliambic version of Babrias. —

This MS. was found to be divided into two books, the one containing a hundred and twenty-five, and the other ninety-five fables. —

This discovery attracted very general attention, not only as confirming, in a singular manner, the conjectures so boldly made by a long chain of critics, but as bringing to light valuable literary treasures tending to establish the reputation, and to confirm the antiquity and authenticity of the great mass of Aesopian Fable. The Fables thus recovered were soon published. —

They found a most worthy editor in the late distinguished Sir George Cornewall Lewis, and a translator equally qualified for his task, in the Reverend James Davies, M.A., sometime a scholar of Lincoln College, Oxford, and himself a relation of their English editor. —

Thus, after an eclipse of many centuries, Babrias shines out as the earliest, and most reliable collector of veritable Aesopian Fables.

The following are the sources from which the present translation has been prepared:

Babrii Fabulae Aesopeae. —

George Cornewall Lewis. Oxford, 1846.

Babrii Fabulae Aesopeae. —

E codice manuscripto partem secundam edidit. —

George Cornewall Lewis. London: —

Parker, 1857.

Mythologica Aesopica. —

Opera et studia Isaaci Nicholai Neveleti. —

Frankfort, 1610.

Fabulae Aesopiacae, quales ante Planudem ferebantur cura et studio Francisci de Furia. Lipsiae, 1810.

Ex recognitione Caroli Halmii. —

Lipsiae, Phaedri Fabulae Esopiae. —

Delphin Classics. 1822.

GEORGE FYLER TOWNSEND

- A History of the Literature of Ancient Greece, by K. O. Mueller. —

1.《古希臘文學史》,K·O·米勒著。 —

Vol. i, p. l9l. London, Parker, 1858.

- Select Fables of Aesop, and other Fabulists. —

2.《選集:伊索寓言及其他寓言作品》。 —

In three books, translated by Robert Dodsley, accompanied with a selection of notes, and an Essay on Fable. Birmingham, 1864. P. 60.

- Some of these fables had, no doubt, in the first instance, a primary and private interpretation. —

3. 這些寓言中的一些無疑最初有一個主要的私人解釋。 —

On the first occasion of their being composed they were intended to refer to some passing event, or to some individual acts of wrong-doing. —

Thus, the fables of the “Eagle and the Fox” and of the “Fox and Monkey’ are supposed to have been written by Archilochus, to avenge the injuries done him by Lycambes. —

So also the fables of the “Swollen Fox” and of the “Frogs asking a King” were spoken by Aesop for the immediate purpose of reconciling the inhabitants of Samos and Athens to their respective rulers, Periander and Pisistratus; —

while the fable of the “Horse and Stag” was composed to caution the inhabitants of Himera against granting a bodyguard to Phalaris. —

In a similar manner, the fable from Phaedrus, the “Marriage of the Sun,” is supposed to have reference to the contemplated union of Livia, the daughter of Drusus, with Sejanus the favourite, and minister of Trajan. —

These fables, however, though thus originating in special events, and designed at first to meet special circumstances, are so admirably constructed as to be fraught with lessons of general utility, and of universal application.

Hesiod. Opera et Dies, verse 202.

4. 赫西奥德的《工作和日子》,第202行。 Aeschylus. Fragment of the Myrmidons. —

5. Aeschylus《蚁人》片段。 —

Aeschylus speaks of this fable as existing before his day. —

See Scholiast on the Aves of Aristophanes, line 808.

- Fragment. 38, ed. Gaisford. —

6. 片段。38,Gaisford编辑。 —

See also Mueller’s History of the Literature of Ancient Greece, vol. —

i. pp. 190-193.

- M. Bayle has well put this in his account of Aesop. “Il n’y a point d’apparence que les fables qui portent aujourd’hui son nom soient les memes qu’il avait faites; —

7. 贝尔将这一点很好地写在了他对伊索寓言的描述中。“现在以他的名字所称的寓言并不是他当年所创作的; —

elles viennent bien de lui pour la plupart, quant a la matiere et la pensee; —

mais les paroles sont d’un autre. —

” And again, “C’est donc a Hesiode, que j’aimerais mieux attribuer la gloire de l’invention; —

mais sans doute il laissa la chose tres imparfaite. —

Esope la perfectionne si heureusement, qu’on l’a regarde comme le vrai pere de cette sorte de production. —

” M. Bayle. Dictionnaire Historique.

Plato in Ph?done.

8. 柏拉图,《斐多篇》。 Apologos en! misit tibi

9. 我给你寄来寓言故事,

Ab usque Rheni limite

Ausonius nomen Italum

Praeceptor Augusti tui

Aesopiam trimetriam;

Quam vertit exili stylo

Pedestre concinnans opus

Fandi Titianus artifex.

— Ausonii Epistola, xvi. 75-80.

- Both these publications are in the British Museum, and are placed in the library in cases under glass, for the inspection of the curious. —

10。这两个出版物都收藏在大英图书馆,并放置在玻璃柜里供好奇者查看。 —

ll Fables may possibly have been not entirely unknown to the mediaeval scholars. —

There are two celebrated works which might by some be classed amongst works of this description. —

The one is the “Speculum Sapientiae,” attributed to St. Cyril, Archbishop of Jerusalem, but of a considerably later origin, and existing only in Latin. It is divided into four books, and consists of long conversations conducted by fictitious characters under the figures the beasts of the field and forest, and aimed at the rebuke of particular classes of men, the boastful, the proud, the luxurious, the wrathful, &c. —

None of the stories are precisely those of Aesop, and none have the concinnity, terseness, and unmistakable deduction of the lesson intended to be taught by the fable, so conspicuous in the great Greek fabulist. —

The exact title of the book is this: —

“Speculum Sapientiae, B. Cyrilli Episcopi: —

alias quadripartitus apologeticus vocatus, in cujus quidem proverbiis omnis et totius sapientiae speculum claret et feliciter incipit. —

” The other is a larger work in two volumes, published in the fourteenth century by Caesar Heisterbach, a Cistercian monk, under the title of “Dialogus Miraculorum,” reprinted in 1851. —

This work consists of conversations in which many stories are interwoven on all kinds of subjects. —

It has no correspondence with the pure Aesopian fable.

Post-medieval Preachers, by S. Baring-Gould. Rivingtons, 1865.

《后中世纪的传教士》,作者S. Baring-Gould。 Rivingtons出版,1865年。 For an account of this work see the Life of Poggio Bracciolini, by the Rev. William Shepherd. —

有关这部作品的介绍可参阅威廉·谢泼德牧师的《波吉奥·布拉乔里尼尼传》。 —

Liverpool. 1801.

- Professor Theodore Bergh. See Classical Museum, No. viii. —

14. 教授西奥多·博格。见《古典博物馆》,第八期。 —

July, 1849.

- Vavassor’s treatise, entitled “De Ludicra Dictione” was written A.D. 1658, at the request of the celebrated M. Balzac (though published after his death), for the purpose of showing that the burlesque style of writing adopted by Scarron and D’Assouci, and at that time so popular in France, had no sanction from the ancient classic writers. —

15. 瓦瓦索尔的著作《论滑稽辞》是在1658年应著名的巴尔扎克先生之邀撰写的(虽然在他去世后出版),旨在证明法国当时流行的斯卡龙和达苏西采用的滑稽写作风格并没有古典文学作品的认可。 —

Francisci Vavassoris opera omnia. —

Amsterdam. 1709.

The claims of Babrias also found a warm advocate in the learned Frenchman, M. Bayle, who, in his admirable dictionary, (Dictionnaire Historique et Critique de Pierre Bayle. Paris, 1820,) gives additional arguments in confirmation of the opinions of his learned predecessors, Nevelet and Vavassor.

16. 法国学者巴伊勒在他出色的词典《彼埃尔·巴伊勒的历史与批评词典》(巴黎,1820年)中,进一步证明了他的学术前辈尼韦莱和瓦瓦索尔的观点,并为巴布里亚斯的主张提供了有力支持。 Scazonic, or halting, iambics; —

17. 斯卡佐尼卡韵律,或者说跛行的抑扬格; —

a choliambic (a lame, halting iambic) differs from the iambic Senarius in always having a spondee or trichee for its last foot; —

the fifth foot, to avoid shortness of meter, being generally an iambic. —

See Fables of Babrias, translated by Rev. James Davies. —

Lockwood, 1860. Preface, p. 27.

See Dr. Bentley’s Dissertations upon the Epistles of Phalaris.

18。参见本特利博士关于法拉利斯书信的论文。 Dr. Bentley’s Dissertations on the Epistles of Phalaris, and Fables of Aesop examined. —

19。本特利博士关于法拉利斯书信以及伊索寓言的论文。 —

By the Honorable Charles Boyle.